BCL

Die Anfänge.

Hier finden Sie historische Bücher!

Hier finden Sie historische Fotografien!

15.01.2011

Source: the star online

Reminiscence

Jungle paradise in the South Pacific

By Tan Wee Kiat

An old-timer reminisces about an engineering assignment he took on once upon a time in the South Pacific.

The South Sea island in question is Bougainville, which was part of the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific before World War I. From April to October 1966, it was my highland paradise.

I was hired to work there as a mining engineer. To get to Bougainville, I was given a long and curious route — by plane from Kuala Lumpur to Singapore, and then on to Perth. Then by rail for two days across the continental desert from Perth to Melbourne.

Here, I had to admit my four-year-old daughter into the ICU of Melbourne Hospital because the trans-continental train gave her gastroenteritis. Afterwards, I got my wife and daughter settled down in an apartment.

Then it was on with the journey: a plane to Sydney, then a commercial flight to Papua New Guinea, landing in Kieta on Bougainville. During my winding journey there, I got hold of Nietzche, a 700-page volume called The Portable Nietzche. It was lying on a seat, discarded or forgotten by a traveller departing Sydney airport.

So with only Nietzche in my hand, I left Australia and headed northeast into the relatively unknown Papua New Guinea — and cannibals!

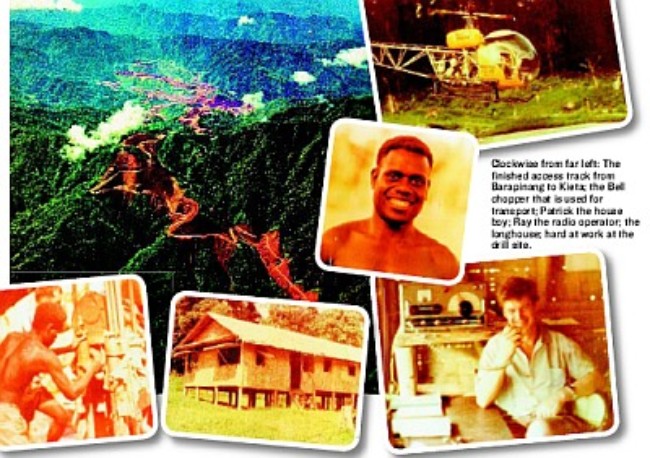

The plane landed in the late afternoon on the airstrip of Kieta. Very early the next morning, Rio Tinto’s Bell helicopter whisked me — a sole passenger — off towards the mountains and away from the many conventional “wants”. Once in the aircraft, I was totally in the “Rio Tinto system”. No one told me where I was being taken or what I would be doing. It was thrilling — actually unnerving — to be helplessly lifted off the ground and flown above the fast-rising mountains.

I could see all this because the chopper had a see-through bottom. After a “long” time and many miles, it became apparent we were heading towards a large clearing. It was a welcome and beautiful oasis in the midst of a dense jungle. I got out of the helicopter and, with body bent low to avoid the whirling blades, headed for the main building.

It was a neat thatched hut like all the others, but larger and with a verandah. The chopper, the instant I was clear of its blades, rose from the ground and departed. Once it disappeared, the loud silence and the cool spring-fresh air hit me — pleasantly.

Ray, a genial and always-smiling German, was engaged in short-wave radio talk when I entered the “mess”. He was the 24-hour-guardian of the radio. He was also the de-facto camp supervisor. During a break in his radio talk, he gave me a quick “briefing” on the place.

Patrick, the “Number One and also ever-smiling House Boy”, carried my things to the long house and dropped them in my room. There were altogether some 14 rooms in the longhouse, and they were only for diamond drill operators. Patrick also showed me the camp facilities: food store, kitchen, hot showers, laundry, etc.

This oasis, called Barapinang, was the base camp established to support and service the men who operated the diamond drills in the area. Within two years, up to July 1968, over 64km of holes were completed by the men to bring up, from deep in the ground, data sufficient to change the status of the copper-gold ore-body from “prospect” to “potential mine” with proven ore reserves.

The first drill was human-carried to site in 1965. Soon after that, choppers were hired to move heavy equipment.

When I was at Barapinang, I found the services excellent. Even the scenery, nearby and distant, were beautiful. The Barapinang base-camp facilities were set up adjacent to a long-existing native village. It was a natural meeting place in the forested mountains. It was also a walk-through “highway” in the jungle.

Diamond drilling was carried out deep into the ground to bring up rock-cores to be evaluated according to type and metal (gold and copper) content. The men operating the diamond drilling operations were a hardy and special breed. They were focused only on getting out as much successful rock cores as possible. They did not want unnecessary talk. They were after good “footage” and the better money that came with it.

They got up very early in the morning, walked along jungle tracks to their own drill sites, finished what drilling they had to do . . . and I don’t know what they did after that. Perhaps they retired to bed in the long house. I never saw them hanging around. I saw them only when I went out of the way to seek them as part of my work. I respected their need for privacy.

Even in the long house which we shared, I never went or looked inside beyond my front room and the entrance. This privacy was also what I liked.

Transportation at Barapinang was restricted to steep jungle tracks — always kept in good repair — and log-bridges across streams. Only for long distance travelling and moving heavy equipment did we use the hired Bell choppers, which cost Rio Tinto a pile, on an hourly basis.

While I was still there (mid-1966) a huge Sikorski helicopter was used to bring up the dismantled parts of a bulldozer. The parts were put back together while still in the chopper pad.

The Caterpillar then started bulldozing a temporary access track down to the coast. This was completed in mid-1967. The result can be seen in Rio Tinto’s magnificent photo. It shows the completed temporary access track and the spectacular nature of the terrain at Bougainville about mid-1967.

But Barapinang, the oasis, was swallowed up by later mining activities. My highland paradise was no more. I hope it remains a treasure in the hearts of the others who also enjoyed Barapinang.